Bite on the Nail

The best advice on writing I ever got. Part 1

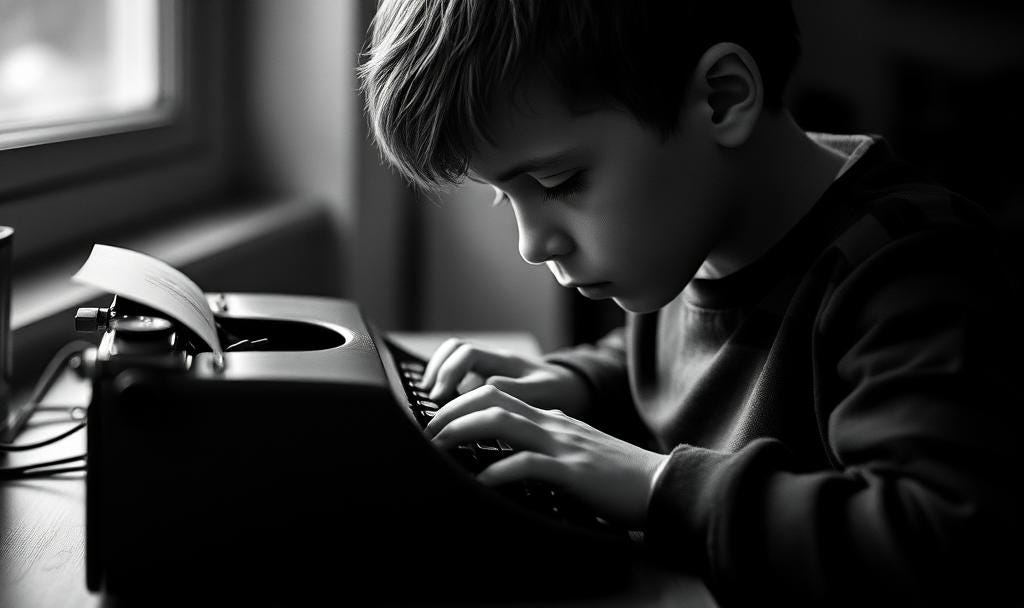

I have wanted to be a writer for as long as I can remember. At least since the age of five when I bashed out The Adventures of Paul and Tim on my dad’s old manual typewriter (I want to say that it was a Corona, but I am not sure, and dad is long gone now, so I’ll never know.)

The question I often ask myself, so many years later, is why? God knows it’s a tough way to make a living, and most of us who call ourselves writers need to do other work to support ourselves and our families. Thinking back, I know now that the original little pulse of light - this is what I want to be - came from reading. And specifically, it came from reading about adventure.

As a child, I began to equate those two things, bind them together. Reading opened up the whole world. It was all there, my dad told me, all the places and times and people, waiting to be explored. For me, that was the first big realisation; that it was real. Even the fiction. Especially the fiction.

And if it was real, then I could be the one doing the exploring. I could be the one doing the writing. All I had to do was get out there and do it. Now that sounded like an adventure, and for me, it changed everything.

In my fifth novel, Turbulent Wake, the protagonist looks back on his life:

When the old engineer had been a young man, just starting his life, when all of what was to come still lay hidden and when everything was still possible, he had decided that he would be a writer.

He had read Tolstoy and Sholokov and some of the other great Russian writers, and for a time had been enamoured of Hardy and then Balzac and the war poets, Graves and Sassoon and Remarque. There was so much to read, and all that men and women had ever felt or dreamed or wondered seemed to be there for his consideration and reflection. Later, he had discovered Hemingway and Joyce and Lawrence and Conrad and dos Passos and Huxley and Orwell, and at twenty he knew he wanted to be a writer.

Of the reasons for this, it would take him many more decades to understand, to finally break apart into constituent elements and see the forces between them and the gravity that controlled his own thoughts and the deeper forces that were beyond thought. But at twenty, with his life still unbounded and nothing but horizon to guide him, he came to the resolution that he would be a writer. That fall he did not register for his second year of engineering studies at the university, but took the money he had earned over the summer working on the rigs in Texas and rented a room in a crumbling turn of the century house in the old part of Calgary, armed himself with notebooks and pencils and an old typewriter, and he became a writer.

Every morning he got up and he wrote. He filled notebooks with ideas, and pages with prose. He could write the words, string together sentences and paragraphs, and sometimes what he had written seemed well-formed, and even, occasionally, worthwhile. But he found, after a time, that his writing was empty, without substance. He had nothing to offer. He didn’t know anything. He hadn’t lived. Even when he tried to write about his childhood, about his brother and the things he had seen on his travels with his parents, he found that the events themselves were not enough. It was as if everything he wrote was shell, and there was nothing inside.

Mark Twain said: “write what you know.” Later, Hemingway, who was a great disciple of Twain, added to this, asking himself: “what did I know about and truly care for the most?” Much later, Martin Amis perfected the thought: “write what you know so you don’t have to write what others already have.” The young man he was knew nothing. He did not know what he truly cared for the most. And everything he wrote was a copy of what others had done, and done better.

He knew it wasn’t a matter of trying. Of putting in the time. Some were able to write as if they had been formed with the knowledge and memories and wisdom of many lifetimes already stored within. Rimbaud completed his entire oeuvre before his twentieth birthday. But at this same point in his life, the young man came to know that before he could write, he needed to live. He also began to fear that perhaps he did not have the talent, and that he was deluding himself.

And so, he decided to live. He decided to find what he cared truly for.

Much later, when the knowledge and timing of his end and the reasons for it were made clear to him, he came to understand that for him it had always been a battle between what he knew and his ability to write it. In his engineer’s way, he pictured it as a graph with time as the abscissa – birth on the left, death on the right. One curve started quite flat and turned sharply into a steep climb at adolescence, peaking and falling away just before death. This was what he knew. The other curve stayed dead flat until sometime in his twenties, and then it slowly started climbing. This curve was his ability to write it. The question was, would his writing ability catch up to his knowledge of life, and leave enough time to produce something?

Each of us is provided the briefest allotment of time. Behind us is all of history, ahead, a fathomless eternity, to the dying of the last stars. In our lives, there is so much we don’t get to choose. Where we were born and to whom. The times we live in. But as human beings, we have will. We can decide how we will face our days, and we can fight for the future we want. So, if you want to be a writer, the one thing, the only thing you have to do, is write.

Hemingway famously said that the secret to writing was to “work every day. No matter what has happened the day or night before, get up and bite on the nail.” I think it’s the best advice on writing I ever got. Maybe it’s the best advice on life I ever got.

Subscribed and will enjoy following. Cheers from Jeddah.

This quote you shared was my absolute favourite part of reading your novel "Turbulent Wake"! It really resonated with me and thank you for sharing it here again with us. Excellent advice on writing and life that I have been trying to follow. It has really sparked a change in my own novel - it went from an idea I was mildly inspired by to something so deeply personal it scared me a bit. Welcome to Substack and looking forward to more writing from you!